The only way to truly see yourself

is in the reflection of someone else’s eyes.

~ Voltaire

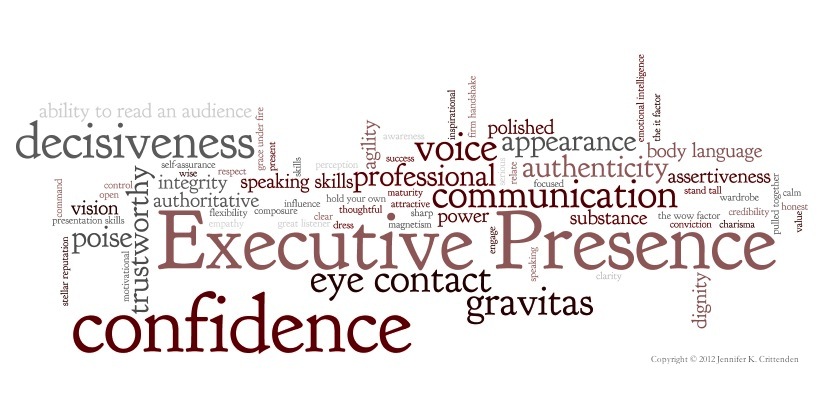

Have you ever heard someone say “I can’t describe presence, but I know when I see it?” For many, defining a strong presence is quite difficult. They may lack the vocabulary to describe its elusive nature. Nevertheless, they, particularly employees when they are evaluating their leaders, can be amazingly astute at judging someone’s character based on a presentation, an interview, or a casual conversation. Employees notice every little thing about their executives—whether they seem ill at ease, if they are spinning something, if they appear defensive, and on and on. As human beings, we are astoundingly observant and critical of subtle behaviors that convince us “she has it,” or “she doesn’t have it.” That’s why I say we are experts about the presence of others.

It may turn out that we are extraordinarily expert about others. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by a researcher at Oregon State University reported that participants were able to correctly identify the genetic makeup of complete strangers after observing them on video for 20 seconds with the sound off. The subjects on camera simply sat and listened to another person tell a story. Participants then rated them for how kind, caring, and trustworthy they seemed. Those results were compared with genetic tests of the subjects, particularly what variants they carried of the oxytocin receptor gene (oxytocin is sometimes referred to as the “love hormone” because of the role it plays in social behaviors). People with the GG variant of the gene tend to be more empathetic, and those with at least one A variant are believed to struggle more with social skills. Participants were able to correctly identify 60% of those with the GG variant, and 90% of those with at least one A variant. That was quite a remarkable feat.

In judging ourselves, however, we may be blissfully unaware of how we come across. When we think we are hiding something very well, we might be surprised at how easily others see through us. We may make great bombastic statements to fire up the troops, but too often they think we are overreaching and are unnerved by our apparent lack of confidence. We must recognize that our self-awareness is fundamentally limited. We are eternal students of our own presence.

Blinders and Earmuffs

A cornerstone of Jean-Paul Sartre’s philosophy of existentialism is that other people reflect our image and that we can only know ourselves through that reflection. Only by seeing ourselves through the eye of the Other, through the judgment of an objective outsider, do we see who we really are. The Other, therefore, represents our mirror. For example, a man looking through a keyhole is preoccupied with what he sees until he hears a creak in the floorboard behind him and becomes aware that another person has entered the room and is observing him. He suddenly realizes what he looks like in the eyes of that person and recognizes what he is—a Peeping Tom.

With that imagery in mind, we can see how useful and important other people’s impressions can be to us. One could ask if we even have a presence if no one is around to feel it. If we make it safe for them to provide feedback, we can learn a lot. The key to evaluating our presence is to observe its impact on others. Being willing to objectively evaluate ourselves is the first step.

The ability to step outside ourselves and look through a different lens is tremendously valuable in building our presence. Empathy, the ability to understand and share the feelings of others, seems to come more easily to some of us, but with practice, we can get better at it. Thinking back over a situation and reviewing how our behavior must have looked to an observer gives us a new angle on our presence. I describe this process as having the blinders fall from our eyes and the earmuffs from our ears as we start to hear and see ourselves as others do.

That new capability leads to keen observation and identification of patterns of behavior between your colleagues or family members and you. As we begin experimenting with conscious adjustments to our usual behaviors, we see the impact play out. Small changes at this point can have big effects. Because feedback and rewards begin immediately, travelers on this journey are motivated to make more adjustments and try new things. Pearl Cleage writes in the novel What Looks Like Crazy on an Ordinary Day, “Once you get that first glimpse of another way of looking at things, you can’t get enough.” Not every reaction will be positive, but once the blinders and earmuffs are off, transformation can happen pretty fast. One step leads to another.

This realization brings us Principle #2:

Our ability to see ourselves through another’s eyes increases our capacity for change.

Creating exceptional presence requires developing sensitivity, raising self-awareness, improving our ability to read others, and building skills to behave in ways that are novel but can be practiced until they are more natural. Those skills permit us to take measured risks, increasing the likelihood of positive reactions, which gives us hope we are on the right path. Discovering our ability to change makes us thirsty to do so, and our desire increases as we sense the utility of the power we now possess.

Nevertheless, let’s be clear. Change is hard. Even though we are working on behavior modification—not a character transplant—accepting someone else’s judgment about us can be a bitter pill. In the You, Not I method, preference is given to the You, the Other, and we are forced to give up our subjective viewpoint, the I in You, Not I. That requires humility and toughness.

A professional presence, even exceptional presence, relies on a set of discrete, teachable skills. If no concerted effort is made to nurture those skills, a professional will typically develop presence slowly through trial and error, learning what works and what doesn’t and attempting to apply their natural talents for better or for worse. Some come into the workplace better equipped than others with good powers of observation and sensitivity. Others struggle.

My research, detailed in Chapter Four, shows that a strong presence is more correlated with education and age than with seniority. Without training, even senior leaders lack confidence about their presence. A focused program can shortcut years of inefficient experimentation and drive straight to the heart of the matter by exposing and analyzing attitudes and insights from others. In my experience, anyone who is motivated and open to change will enhance their presence in a matter of months, not years.

© 2014 Jennifer K. Crittenden

Ten 90-minute individualized sessions. Private and confidential.

Ten 90-minute individualized sessions. Private and confidential.