To impress someone with your presence, you have to do more than just show up. You have to allow them to feel your presence. And a big part of that is actually being present, not just with your body, but with your mind. Another word for this is mindfulness or wise attention. Your brain is fully engaged in the moment and an active participant with what is happening around you. All your sensory perceptions are on high, and your focus is on the people and happenings in your environment. As Yogi Berra said, “You can observe a lot just by watching,” and this article will explore the many benefits of heightening your powers of observation, awareness, and concentration on now.

When hip young Brits and Americans, including Jack Kerouac, the Beatles, and the Grateful Dead, encountered Zen and Buddhism in the sixties and seventies, they discovered new ideas about how to relate to their surroundings. Instead of imposing, dominating, and controlling, they began to consider letting life come to them. Yoga scholar Ram Dass’s advice in Be Here Now was unconventional, and numerous books and songs explored a more passive and accepting attitude to events in your life. Caught in a traffic jam? Embrace the moment. Experience the event. In the throes of a breakup? Accept this transition period and learn what you can from it. Employed in a menial job? Perhaps there’s a certain beauty in laying roof tile or serving food to others. That attitude would provoke a certain amount of eye-rolling today, but I would suggest that there is still something to glean from this that could make our modern life a bit happier.

When we open ourselves up to the present, we allow ourselves to set aside judgment for a few moments. We no longer have to confront the “you should be doing”; instead we contemplate the “you are doing.” In some sense, it’s more honest, humble, and less stressful to consider our actions in that light. The pressure to perform and conform has risen over the past few decades, and I suspect it has led to much unhappiness. It is worthwhile to step back, if only for a few moments, and consider the ramifications of letting go of the should and entering the world of being.

Suppose that you arrive at a meeting and discover that an important visitor has been detained. Not only can the meeting not start until he or she arrives, the cause of the delay and how long it will last is unknown. Most leaders would be instantly frustrated in such a situation. They would attempt to track down the visitor, storm from room to room, question everyone in sight about what they know, when the delay will end, and what the prospects are for solving this problem. What if you took a different approach? What if you said to yourself, “This is a rare opportunity for me to interact with the other people in this room while I have time and while they are in my presence?” I admit, it sounds a bit radical, but bear with me.

Now picture yourself circulating amongst the participants and saying, “Well, why don’t we catch up for a minute. I don’t get a chance to meet with you often, so let’s take advantage of this delay. How is your day going?” How do you think they would react? Even if they are shy, even if they are surprised, even if they didn’t expect this, will they be pleased? You bet your fanny they will be. People love to be acknowledged by their leaders. Surprise them. Be gracious. Be calm. Be here now.

It’s easier said than done, and that’s why you must practice, just as you must practice many aspects of a strong presence. First you must quell the preoccupation that is obsessed with having things go other than the way they are going. The meeting isn’t going to start on time? Let it go. You have another appointment in an hour? That will resolve itself. Life happens. What you don’t want to do is wreck this moment because you’re worried about that moment. Then everyone loses, and important time is lost.

Choosing to spend time with someone, particularly when it is unplanned and spontaneous, sends an important message. It says, “I welcome a chance to interact with you, and I got lucky. Thank goodness this other thing happened so that you and I can talk.” Instead of slamming out of the room and communicating that no one present is worth conversing with when the guest of honor isn’t there, you convey your interest in talking to those present instead. What a flattering and respectful message to send.

Now that you appreciate the opportunity you have been given, open yourself up to the moment. Open your eyes and ears. Slow down. Make silent observations about your companions. Listen. Concentrate on the moment. Focus on your conversation partner. Set yourself the practical challenge of memorizing what they say so well that you can repeat it to yourself verbatim later. Pay attention to their faces and their names. If you start over-nodding impatiently as you attempt to break into their narrative, still yourself and stay in the moment. Set aside your other thoughts and try to put your whole body and mind into the moment. If you can recreate later exactly how you were feeling, the visceral physical sensation of that flash in time, you know you have done well.

Be careful not to send messages that reveal that you are just faking it and are not really in the moment. Don’t let your eyes glaze over as someone tells you about their troubles, don’t glance impatiently on to the next person you ‘have to’ talk to, don’t let your mind wander. Those subtle signs of inattention will not be missed by your conversation partner and will disappoint him or her.

Improvisational training can help you practice the habits of being present. Tina Fey proposes in Bossy Pants that the world would be a better place if we all learned the improv rule of “Yes . . . and.” It teaches you flexibility and how to go with the flow. It helps you “stay out of your head,” as the actors say, and learn to move from moment to moment without second-guessing and backing up. Playing a musical instrument and other performance techniques will also help you just keep going, even if you’ve made a mistake or have an off moment. A colleague told me resolutely one day, “Today is a day when I smile and nod a lot.” I think of that when things go wrong.

Yoga practice can also strengthen your ability to focus by relaxing your mind, concentrating on breathing, making you more sensitive to subtle sensations of the body. Like meditation, yoga helps you relax and give your brain a break from racing around as it usually does.

The payoff from waking up and paying attention to your surroundings can reap significant benefits. When I suggested to one client that she practice being present during her morning commute, she discovered that she was taking an inefficient route to work and could cut five minutes off her travel time. Another noticed that her company’s parking lot was located quite close to a former colleague’s building and they could easily go to lunch together. What great rewards!

In the spirit of Zen, however, being present is its own reward. By focusing on and accepting the moment, you appreciate it. You can relish its immediacy and enjoy whatever life is presently offering you. It makes life more interesting and makes you more interesting. Your comfort with the moment is contagious and makes you easy to be around. It expands your aura, as others are drawn to you. If you are a full participant, apt observer, and engaged enthusiast of the here and now, you are very clearly present.

Copyright © 2013 Jennifer K. Crittenden

Sign up for an individualized program to enhance your own Presence:

Creating Exceptional Presence

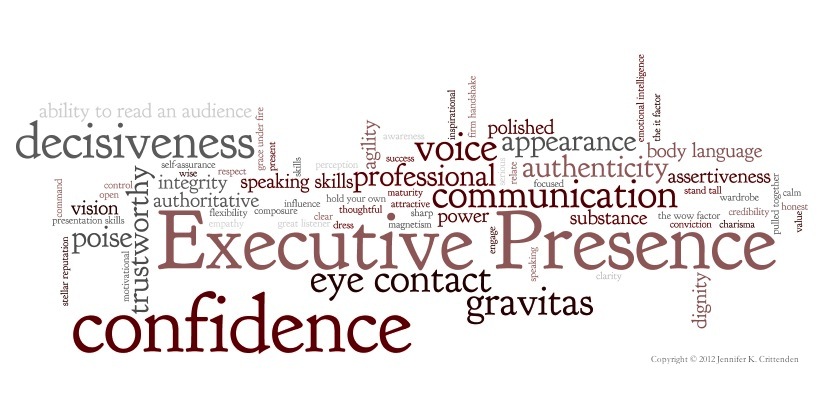

The program includes self-assessments of areas related to authority, credibility, authenticity, trust, composure, and confidence. Tactical lessons include voice, body language, social and language skills. Context-specific behaviors are identified, studied, evaluated, and practiced. Individual coaching is provided in six 90-minute video-Skype sessions, followed by readings and exercises, including audio and video analysis of self and others. Participants will receive Crittenden’s new handbook Creating Exceptional Presence (Whistling Rabbit Press, 2014), addressing such topics as behaviors versus perceptions, derailers, stage fright, and pre-performance rituals. Program time totals 56 hours, typically over three months. The introductory cost is $2000. More information here.

Ten 90-minute individualized sessions. Private and confidential.

Ten 90-minute individualized sessions. Private and confidential.